When my children were four and eight, they were briefly enrolled in the “best” public elementary school in Broward County. They had previously attended a wonderful Montessori school, but we had moved to Florida so that I could launch a middle school for highly gifted children. After a few weeks, they complained that the school was a “learning prevention center.” Their mother and I went to visit the school at lunch, and within 30 seconds of observing the pandemonium of the lunch room, we pulled them out.

I was working long hours building a new school and their mother was suffering from a chronic disease that left her bedridden much of the day. Other than a fabulous math program that my son attended twice per week, they mostly read books and played; “unschooling,” if you will. But they both had terrific focus from their time at the Montessori school, where a three hour “uninterrupted work period” each morning had been core to their routines.

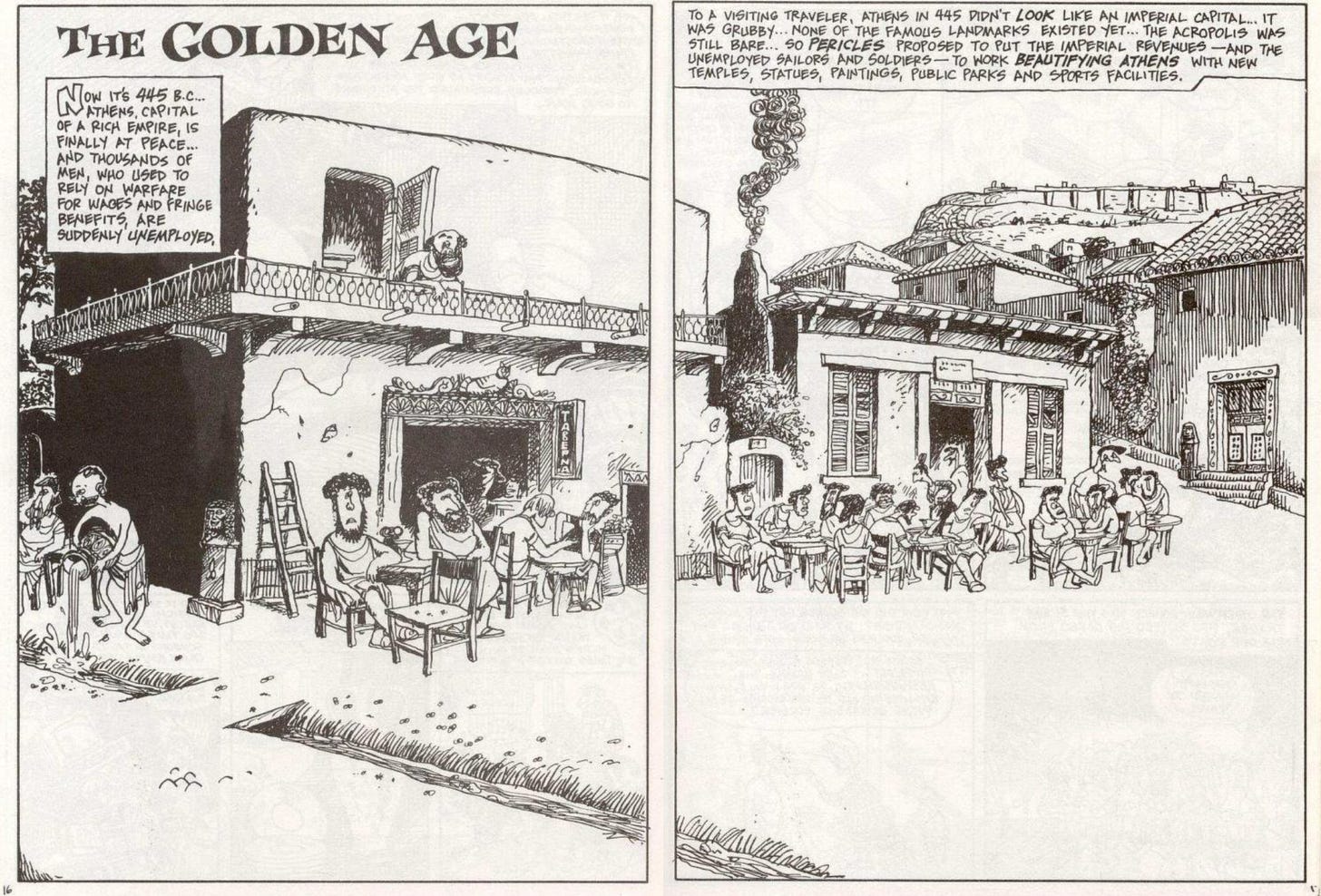

The first book my son read was Larry Gonick’s “Cartoon History of the Universe,” an irreverant but sophisticated cartoon history. I compared it to the 4th grade history textbook he had been assigned at school. The history textbook, as with most history textbooks, was boring, bland, tedious garbage.

No one would ever read it for fun, and if they were forced to read it, as they were at school, the wouldn’t remember anything. Meanwhile, Gonick was piling provocative story upon provocative story, with fun anecdotes that my son and I would laugh about together.

Optimizing for Focus and Engagement

After thirty five years in education, most ed policy discussions strike me as insane. In the 1990s I spent hundreds of hours going into hundreds of public school classrooms across the U.S. to lead demonstration Socratic Seminars. Especially in middle and high schools, the level of apathy and disinterest most students had in class was appalling - and exactly what I remembered from my years in “high performing” public schools in the 70s. I’ve walked down many miles of cinder block hallways lined with lockers under floorescent lights, observing room after room of students yawning, heads down on desks, others joking or flirting, some staring off into space, and typically only a handful actually engaged in something like learning.

There were exceptions; out of the perhaps 300 schools I’ve visited, perhaps 5-10 of these schools had reasonably high levels of engagement school-wide. Typically they had an inspired leader who had been able to assemble a high quality, aligned staff. But these were the exception; most reflected the more recent data I’ve seen that 66% of students in high school are not engaged in learning and 75% are unhappy at school.

When I would go in to provide a demonstration Socratic discussion, I would optimize for engagement. If I couldn’t get them to be focused and engaged for 60 minutes, then very little productive activity would take place. See here for a leader’s eye view of exactly how I did this in a rough inner city classroom. Within a few days, I was able to get considerably greater intellectual focus going. But the constraints of public schools are too severe to do this at scale, so I’ve given up on them since about 1997.

There I used the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal administered pre and post to evaluate progress. In four months of Socratic Practice, minority females gained as much as the average American student does in four years of high school, on a test highly correlated with the SAT.

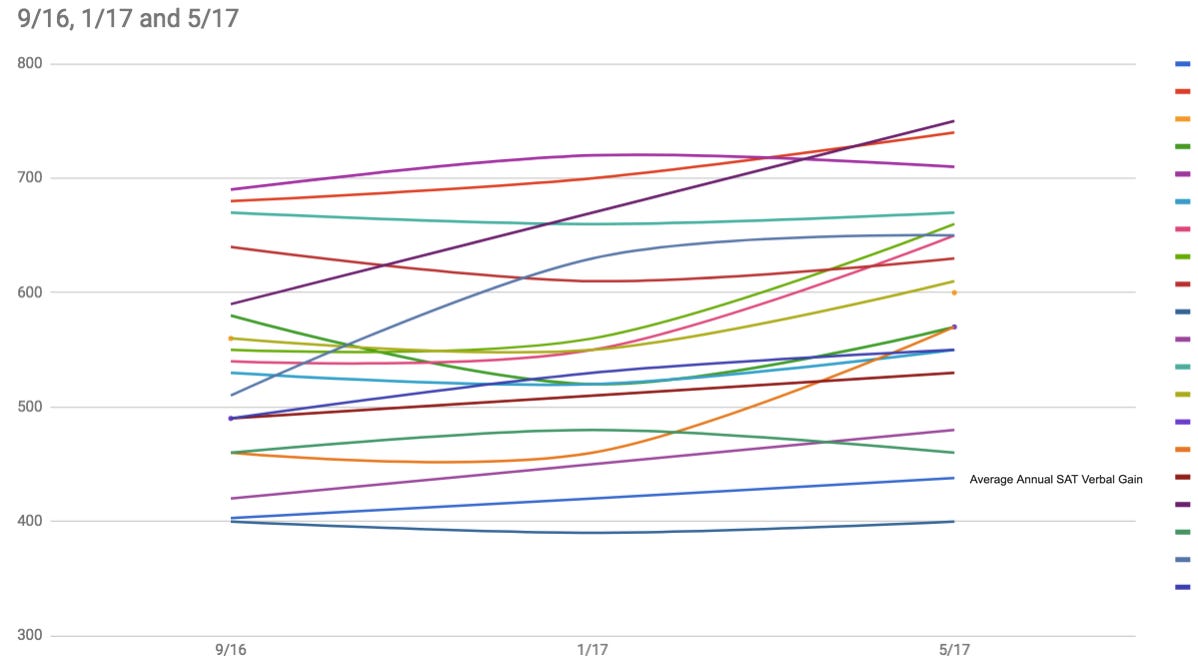

Since then I’ve switched to using the SAT verbal pre and post. At the Khabele-Strong Incubator (KSI), an alternative school I created in Austin,

Average SAT gains for KSI high school students for 2015–2016: 140 points (80 points verbal, 60 points math)

Average SAT gains for KSI high school students who were with us for two full academic years, 2014–2016: 313 points (173 verbal, 140 math)

For comparison purposes, analysis of three large-scale evaluations of SAT coaching concludes that the average student enrolled in an SAT prep course gains 30 points (5–10 points verbal, 10–20 points math).

Morever, my consistent impression of classes that I’ve led is that those students who are most engaged are the ones who gain the most. Once I have the organizational bandwidth, I want to have guides pre-register which students are most engaged and then see if those students register higher SAT verbal gains.

I’m also looking at either eye tracking or facial expression software as technological means of measuring engagement to see to what extent those measures of engagement correlate with significantly higher SAT verbal gains (here I’m focused on the Socratic discussion component, thus the focus on verbal rather than math gains). At scale, the game plan is to formalize such measures of test score gains and measures of engagement.

What Counts as Productive Engagement?

In the realm of learning to read difficult texts, the SAT verbal is a reasonable measure. Moreover, most people would agree that learning to read more challenging material is valuable (regarding the SAT as a reading exam, I’ve found that most students scoring SAT 600 or higher can make sense of Plato, whereas a student scoring 400 or lower will really struggle).

But what about focus in other domains?

Certainly children may focus on legos and video games with an uncertain future benefit (maybe yes, maybe no). On the other hand, students who engage in deep focus for hours per day on math or coding will almost certainly benefit.

What about a focus on building forts? Or musical theatre? Or taking engines apart and putting them back together again?

Most parents accept the standard K-12 school curriculum as worthy of focus. Personally, I regard 80-90% of it as a waste of time. I have huge respect for high level reading, writing, and mathematics skill development. But I see most of language arts in school as consisting of tedious exercise with dubious value. I’d MUCH rather have my children actually reading and writing than doing language arts exercise. Certainly the substance of the mathematics curriculum is by far the most valuable component of standard schooling (imperfect as it is). History? Read real, engaging age level appropriate history. Science? Explore cool science books, articles, and videos until the student has sufficiently high level reading and math to take serious science courses, which don’t begin until high school (though capable middle schoolers can take them at younger ages).

Moreover, I’d much rather see a child spend 30 minutes per day deeply focused on mathematics than an hour dabbling here and there. If they are capable of focusing 1-2 hours or more on serious mathematical problem solving, hallelujah! But if they are not focused, it is better to do shorter bursts.

They can read, discuss ideas, and write several hours per day.

But for most children, after doing sufficient math, reading, and writing, if none of those are their particular passion, I’d encourage a deep focus on something they care about: Coding, building things, designing, creating a business, etc.

A child who is deeply focused on productive activity for several hours per day for years at a time will become likely become amazing at that activity. Yes, much better if their practice at skill building is “deliberate practice.” But the students I’ve known who were remarkable at coding as a teen did so since they were a child; the ones who built incredible businesses were trying out schemes for making money since childhood; the ones who were phenomenal writers were writing stories since they were young; and so forth.

It should not be surprising that if your child is spending five hours per day drawing from age six to sixteen, they would have a remarkable capacity to draw. Given the fact that drawing is not likely to result in a comfortable career, then the question is, “Can the visual perception abilities developed through drawing be transferred to other forms of visual design?” Maybe so, but insofar as there may be uncertainty I’d begin exploring the possibility of other applications with them earlier so that they are thinking of ways to apply their highly developed skills of visual perception to other domains. Even if all visual work is done by AIs in the future, human taste will often be better at developing visuals for particular human beings or businesses for some time to come.

Much of what I do at the high school level is mentoring students in applying their particular genius, developed through years of focused engagement in specific activities, to productive possibilities in the world. I have an expansive sense of how human beings can add value to other human beings, and see us moving to an experience economy (people will value experience) and a transformation economy (people will value transformations).

Once parents and educators leave behind the wasteland of traditional school curricula, they should learn to focus on optimizing children’s engagement in productive activities. One aspect of this is supporting a child’s deep engagement in activities they are drawn to. But another is considering how to apply a child’s interests and aptitudes to creating value in the world. This ultimately means adding value to the lives of other human beings.

Education in the future will be developing young people’s passions so that they engage in such extensive engagement in activities that they will become amazing in their domains (e.g. Steve Martin’s “Be so good they can’t ignore you”) and then guiding young people to pathways where they can be valued in the world and earn an income by applying their genius to provide value to others.

Why so much emphasis on math? What is the benefit for an average person beyond basic geometry and algebra?

As you know Michael, I'm a big fan of this model and I love seeing the gains of directed attention quantified like this. I recently attended a math training program put on by Paul Zeitz, which coincided with my interest in math circles for my kids (although hard to create in person where I am). It offered what I think is a really cool model for providing socratic style investigation in math, one which could sustain attention for a long time and invite a lot more play into math.

One aspect of your students success that I see but which is a little less explicit in your write-up of this is the community and expectations which a good socratic dialogue (or even a bohmian dialogue which I think is pretty similar) requires. The fact that students learn to engage deeply with peers of similar caliber and engagement feels just as important to me (and is maybe the weakest point of what I think I'm doing with my kids).

Great write up (as always). Thanks for sharing.