Image by Aino Tuominen from Pixabay

“In the 1990s, about 40 young elephants were taken a few hundred miles closer to Johannesburg . . .

The male elephants that had been transferred became unusually violent. They were attacking each other much more frequently, sometimes attacking people, pushing cars off the road (which, in a tourist center, is more than a little concerning), but most of all, rebuffed by older females, they were going after female white rhinos, the largest available pachyderm in the neighborhood, and raping them. Then killing them. . . .

When young male elephants approach sexual maturity, they go through a phase called “musth,” where testosterone floods in at up to 60 times the usual levels, making them highly aggressive, irritable and dangerous. This usually lasts a short time — but not for the Pilanesberg Park males: They entered musth earlier and stayed in it longer, much, much longer. Instead of weeks, their frenzies lasted months . . . Why were these episodes happening for so long? Why weren’t they un-happening?

That’s when elephant scientists had a suggestion. In ordinary herds — where there are lots of big, older, respected male bull elephants around — when a teenager goes through his wild phase, he will get slapped down by a larger, older male. The younger male will attack, and when he’s beaten … something chemical happens …

Says J.B.MacKinnon: “After standing down to a dominant bull, the rush of hormones in the younger male stops, in some cases in a matter of minutes.” The cue to turn off the testosterone comes from getting bonked. So biologists suggested reintroducing a group of elders into Pilanesberg.

Six older elephants arrived, did what oldsters do to rambunctious youngsters, and not long thereafter, says MacKinnon, “the killing of rhinoceroses stopped.” The verdict: The young elephants went wild mostly because there were no older elephants around to keep them in check.” (NPR)

Clearly elephants evolved in multi-age tribal groups. When a group of young elephants were isolated, extremely violent behaviors took place. When this particular “evolutionary mismatch” condition was eliminated by bringing in older male elephants, the extreme behaviors stopped. In this particular case, we have a biochemical explanation connecting the return to an environment close to that of evolutionary adaption to a return to more normal behavior — standing down to a dominant bull reduces the hormonal rush in younger males.

Brain Behavior Interactions in Human Puberty

A recent paper by Jiska Peper and Ronald Dahl summarizes the rapidly growing domain of brain-behavior interaction in human puberty:

“. . . there is growing evidence in both humans and animals that pubertal hormones may influence (bias) some neural and neurobehavioral tendencies of social and affective processing. . . .

The fundamental task of adolescence — to achieve adult levels of social competence — requires a great deal of learning about the complexities of human social interactions. Puberty appears to create a neurobehavioral nudge toward exploring and engaging these social complexities. . . .

The model suggests that interactions between social–affective processing systems in the brain and cognitive control systems can lead to healthy adaptation to the complex and rapidly changing social contexts of adolescence. However, these can also lead to negative trajectories such as substance abuse or depression. These negative trajectories may begin as small changes, but over time can lead to patterns of behavior that have cascading effects: brain-behavior interactions with spiraling impact across adolescence.” (bold emphasis added)”

None of this should be surprising. But so far the interactions between an adolescent’s social world and potentially “negative trajectories” has not been adequately explored. Nor have we explicitly considered the relationship between these potentially negative trajectories and the social environments in which adolescents often find themselves.

For instance, the CDC cites “school connectedness” and “family connectedness” as the two strongest protective factors for a wide range of teen dysfunctions. With respect to school connectedness,

“School connectedness was found to be the strongest protective factor for both boys and girls to decrease substance use, school absenteeism, early sexual initiation, violence, and risk of unintentional injury (e.g., drinking and driving, not wearing seat belts). In this same study, school connectedness was second in importance, after family connectedness, as a protective factor against emotional distress, disordered eating, and suicidal ideation and attempts.”

From an evolutionary mismatch perspective, this is not the least bit surprising. If we evolved in small tribal groups in which we would have been tightly connected with our peers, parents, and community more generally, then the experience of disconnection for extended periods of time would be quite unnatural.

Separately, Stanford psychologist William Damon has found that a sense of purpose correlates highly with various measures of adolescent well-being (“PIL” below being one such measure).

“The most common work on purpose is a variety of studies that utilize Crumbaugh and Maholick’s(1967) PIL. In the original study conducted by the authors, results revealed that the PIL distinguishes significantly between psychiatric patient and nonpatient populations. . . . This was the beginning of a trend that looked at the relation between purpose and a number of maladaptive behaviors and outcomes. For example, studies suggest a relation between lower scores on the PIL and drug involvement, young peoples’ participation in risky and antisocial behaviors, and alcoholism. On the more positive side, the PIL has been related to young people’s commitment to social action and is a mediating factor between religiosity and happiness. Thus a sense of purpose is connected to health and productive behaviors in all their manifestations — psychologically, socially, and physically..”

Damon also cites evidence that most teens lack a sense of purpose,

“In a study that followed 7,000 American teenagers from eighth grade through high school, . . . “Most high school students . . . have high ambitions but no clear life plans for reaching them,” . . . They are, in the authors’ phrase, “motivated but directionless.” As a consequence, they become increasingly frustrated, depressed, and alienated.”

Again, from an evolutionary perspective, teens would have had a strong sense of purpose based on the norms of their community. They would have been raised within a coherent meaning system with myths and behavioral expectations to which they were universally expected to adhere.

Adolescence in the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation

Human beings evolved over many millions of years in diverse physical environments. But with respect to social structure, until the dawn of agriculture and empire, almost all adolescents:

1. Lived in a small tribal community of a few dozen to a few hundred with few interactions with other tribal groups.

2. These tribes would have shared one language, one belief system, one set of norms, one morality, and more generally a social and cultural homogeneity that is unimaginable for us today.

3. They would have been immersed in a community with a full range of ages present, from child to elder.

4. From childhood they would have been engaged in the work of the community, typically hunting and gathering, with full adult responsibilities typically being assumed upon puberty.

5. Their mating and status competitions would have mostly been within their tribe or occasionally with nearby groups, most of which would have been highly similar to themselves.

Contemporary adolescents in developed nations, by contrast:

1. Are often exposed to hundreds or thousands of age peers directly in addition to thousands of adults and thousands of electronic representations of diverse human beings (both social media and entertainment media).

2. Are exposed to many languages, belief systems, norms, moralities, and social and cultural diversity.

3. Are largely isolated with a very narrow range of age peers through schooling.

4. Have little or no opportunities for meaningful work in their community and no adult responsibilities until 18 or even into their 20s.

5. They are competing for mates and status with hundreds or thousands directly and with many thousands via electronic representations (both social media and entertainment media).

We do not know for certain exactly which of these differences between our environment of evolutionary adaptation and contemporary adolescence in developed nations result in which manifestations of mental illnesses and to what extent. But it would be surprising if these rather dramatic changes in the social and cultural environment did not have some impact.

Considering Evolutionary Mismatch as a Causal Factor in Adolescent Mental Illness

Around the world as nations become more prosperous, traditional public health concerns such as infant mortality and contagious diseases become less prevalent. At the same time, new public health concerns such as obesity, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes become more prevalent. Daniel E. Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard, explains the role of evolutionary mismatches as a causal factor in the increasing prevalence of such diseases,

“Broadly speaking, most mismatch diseases occur when a common stimulus either increases or decreases beyond levels for which the body is adapted, or the stimulus is entirely novel and the body is not adapted at all.” 169

Lieberman’s book The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, and Disease, is the definitive treatment of such mismatch diseases.

While the book largely focuses on physical diseases, Lieberman recognizes that the same mismatch principle is likely to be responsible for some mental illnesses,

“There is good reason to believe that modern environments contribute to a sizable percentage of mental illnesses, such as anxiety and depressive disorders.” 159

In addition to anxiety and depression, he also adds ADHD, eating disorders, chronic insomnia, and OCD as mental illnesses whose modern prevalence is likely due in part to an evolutionary mismatch.

Evolutionary Mismatch Does Not Exclude a Genetic Causal Component

Type 2 Diabetes is a reasonable analogue to the situation of many mental illnesses. It unambiguously has a heritable component. And yet few would claim that diet and lifestyle are irrelevant to type 2 diabetes. Daniel Lieberman, cited above, uses type 2 diabetes as one of the most compelling examples of an evolutionary mismatch disease — yes, there is a genetic component, but in the environment of evolutionary adaptation far fewer people developed type 2 diabetes.

Analogously, a recent paper that found definitive proof that there was no “depression gene” first acknowledges significant heritability,

“Major depressive disorder (hereafter referred to as“depression”) is moderately heritable (twin-based heritability,∼37%”

But then goes on to conclude that the genetics of depression are complex.

“However, an evolutionary geneticist points out that there are evolutionary reasons why we should not expect to find common genes with significant negative effects:‘Geographically dispersed or common risk alleles are older and more likely to be repeatedly detected . . . But, their widespread dispersion indicates that those alleles are benign (at least in regard to fitness history), so if they are associated with disease the causal finger actually points to recent environmental change rather than primarily to genetic etiology’. This changes the model from a search for defective genes to recognition that many genes causing highly heritable common disorders are normal variations.”

Thus the examination of evolutionary mismatches that may trigger mental illness is a complement to the recognition that some subsets of a population may be more genetically sensitive to the evolutionary mismatch. As always, many outcomes represent a genetic-environmental interaction.

Is Adolescent Mental Illness Due in Part to an Evolutionary Mismatch?

The journalist Johann Hari argues in Lost Connections that depression is caused by the absence of:

1. Disconnection from meaningful work

2. Disconnection other people

3. Disconnection meaningful values

4. Disconnection childhood trauma

5. Disconnection status and respect

6. Disconnection the natural world

7. Disconnection a hopeful and secure future

While some of these disconnections are more robustly supported than others as causal factors in depression, all but the fourth and seventh one may be regarded as evolutionary mismatches (it is not clear that we can make meaningful generalizations about childhood trauma in a world in which death was common, and there is no reason to believe that humans experienced a “hopeful and secure future” in the environment of evolutionary adaptation). But certainly “meaningful” work was the norm, connectedness to other people was the norm, a profoundly coherent system of meaningful values was the norm, most people would have experienced largely stable status and respect hierarchies, and of course they lived in the natural world.

With respect to the chapter on disconnection from other people, Hari cites the work of John Cacioppo, one of the founders of “social neuroscience,” whose work provides extensive physiological documentation of evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson’s simple statement, “People must belong to a tribe.” Cacioppo is explicit in connecting social neuroscience to mental health,

“Social neuroscience is a new, interdisciplinary field devoted to understanding how biological systems implement social processes and behavior. . . .”

In addition to summarizing a significant amount of information on the physiological correlates of mental illness, the article explicitly analyzes the role of social behavior, “Social behavior can be classified into broadly defined subcategories including (a) self-perception, (b) self-regulation, ©interpersonal perception, and (d) group processes.”

The article concludes that the social factors and deficits are both causes and consequences of psychopathology,

“As understanding of the social brain advances, this knowledge can support understanding of mechanisms by which social factors and social deficits operate as causes and consequences of psychopathology.”

From the perspective of evolutionary psychiatry, the fact that social factors and deficits are sometimes the causes of psychopathology should not be the least bit surprising. We are now living in a social environment that is dramatically different from the environment of evolutionary adaptation.

To explore yet an additional direction, Liah Greenfeld is a Durkheimian sociologist who specifically attributes the modern epidemic of depression, bipolar, and schizophrenia to the burden of creating an autonomous identity in the modern world. She argues that in the past few centuries modernity has gradually shifted away from traditional identities that were largely stable over generations to the modern notion of personal identity in which we each are expected to have the freedom and opportunity to create our own identity and pursue our own individual destiny. While this major sociological transition has been incredibly liberating, it has also been an immense and growing burden for which many young people are unprepared.

Again, it is certainly the case that in paleolithic cultures human beings did not have the range, opportunity of choice, or responsibility to create their own identities that they have today. It is noteworthy that Greenfeld sees the Anglosphere as the culture most advanced with respect to anomie. This would explain why Twenge and Haidt find the most severe social media outcomes in the Anglosphere.

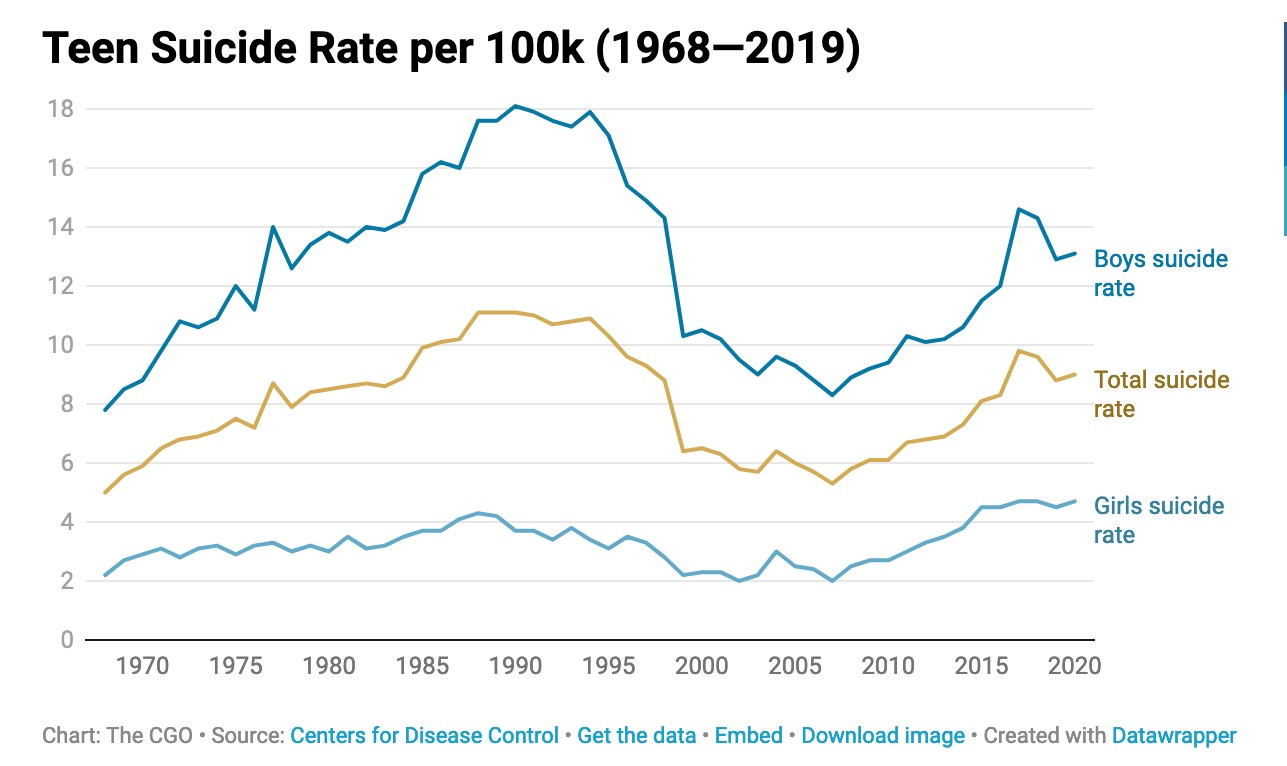

Of course, there are those who question the evidence regarding a modern epidemic of depression, bipolar, and schizophrenia. To avoid the issue of differences in the extent to which these conditions have been recognized and diagnosed over the centuries, we can look at changes in suicide rates. Certainly teen suicide rates increased dramatically in the 20th century. They declined in the 1990s (most likely due to SSRIs) then have been increasing since the early 00s:

After rising to about 400% higher than in the 1950s, then back down to only about 200% higher in the late 90s and early 00s, they are once again approaching 350% higher than the 50s. Might the growth in teen suicides from 1950 to 1990 be a result of an increased evolutionary mismatch during that period?

High School as Evolutionary Mismatch

We don’t know why, exactly, teen suicide increased 400% prior to the introduction of SSRIs. That said, the correlation with schooling is intriguing. For instance, white students completing high school increased from about 30% to about 70% from 1950 to 1980.

From a 2001 article on teen suicide (bottom line represents teens):

If we look at suicide rates age 15–19, white males increase from 3.7 per 100,000 in 1950 to 15.0 per 100,000 in 1980, more than 4x. Female rates did not increase at the same rate: White females age 15–19 went from 1.9 per 100,000 in 1950 to 3.3 in 1980, 1.7x.

For males, at least, the growth in high school enrollment tracks the growth in teen suicides. Is there some proportion of adolescent males who are not thriving in the high school environment? Might these males have felt a great sense of purpose in a work environment while also benefiting from being around adult males?

There are many ways in which the environment in which adolescents today find themselves today differs dramatically from the environment(s) of evolutionary adaptation. It might be:

1. The lack of multi-age groupings (Bull elephants needed?)

2. Small changes leading to cascades of dysfunction (Peper and Dahl)

3. The lack of a sense of purpose through work and survival needs (Damonian possibilities)

4. The lack of human connection (Hari/Cacioppo possibilities)

5. The lack of a shared culture and belief system leading to anomie through a malfunctioning process of identity formation (Greenfeld/Durkheimian possibilities)

These are not mutually exclusive possibilities. Without providing any particular conclusive evidence connecting a particular phenomenon with a particular evolutionary mismatch, for now I simply want to open up the direction of evolutionary mismatch for adolescent dysfunction and mental illness for continued exploration and investigation.

The present paradigm of adolescent mental health takes the existing schooling system as a given. Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge have been emphasizing the rise of smartphones and the decline of free play as causal factors in the recent adolescent mental health crisis. But if our default standard for well-being is the environment of evolutionary adaptation, then we should broaden our exploration for causal factors to include schooling as a dominent influence (for better or worse) on adolescent wellbeing. The evidence that teen suicides increase during the school year, especially on Mondays, is significant. Moreover, this is a seasonal pattern that stops at age 18.

At this point, most teens most of the time are either in school or online. While addressing the digital addiction crisis and free play crisis, we should also be thinking about learning environments.

Can we create learning environments that more deeply satisfy adolescent needs for connection, community, meaning, and purpose? If we take the evolutionary mismatch hypothesis seriously, we clearly should be exploring how to do so.

This definitely rings true to me! When I was young, I assumed that there were “problem children” from dysfunctional families. As long as I was a good, loving parent, my own kids would surely be OK. I was in for a surprise when my son reacted to school pressure and alienation (by teachers and students) by lashing out. Dropping out of school helped a lot, but he's still trying to find his place in the world six years later. A sense of belonging and purpose is missing for so many young people.

As someone diagnosed as an adult when I first got a mostly-WFH email job — I’d love thoughts on how to apply this to adulthood as well!